Jenn Pelly On The Intuitive Feminist Punk Of The Raincoats

No one’s little girl.

There’s definitely something optimistically infectious about The Raincoats’ self-titled debut album. Rhythms and melodies rumble under the surface, breaking through to the listener a sense of other worlds, motions, utterances and possibilities. The exuberance and excitement of collective female energy present on this classic album has been captured by music journalist Jenn Pelly in her new book about the record, The Raincoats.

Reading Pelly’s book brought back so many memories of when my teenage band Kiosk toured the US with fellow all-female band, Finally Punk. The impetus moment of creating a band, and particularly doing it collectively as women, was an unparalleled experience.

The influence of a band like The Raincoats, at the time was perhaps not perceptible. But somehow, as a cult band who were never part of the mainstream, their music still hits hard as a work of huge guidance and unwavering affirmation.

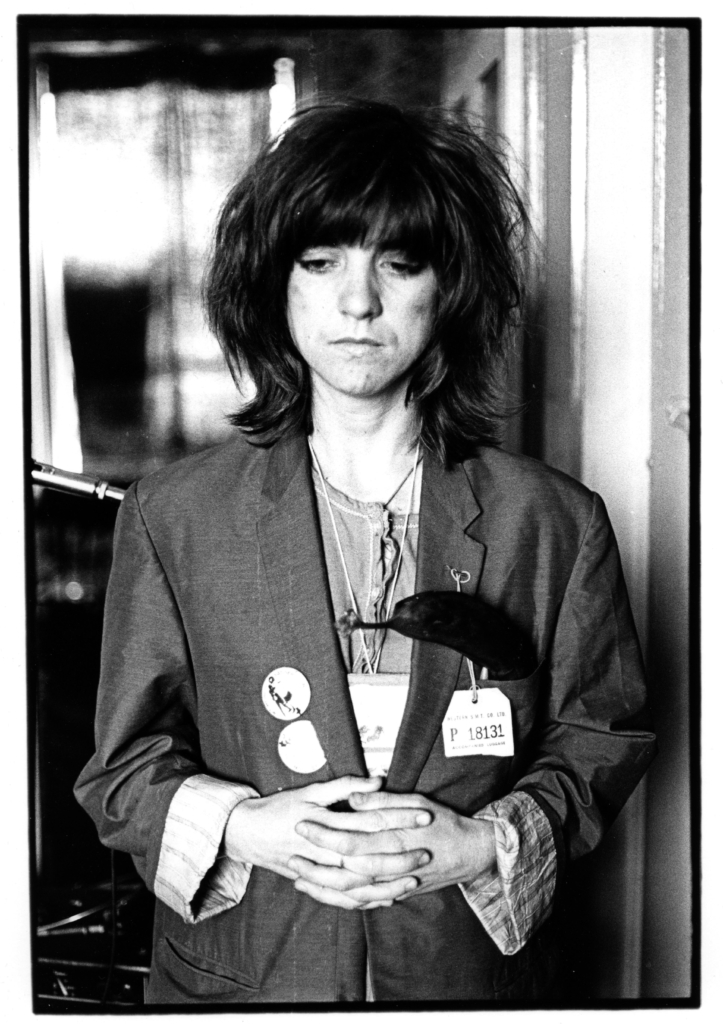

Angie Garrick: Your book ties together a global feminist lineage of punk. You mention Yoko Ono, Patti Smith, The Slits, Bikini Kill, my favourite, Marine Girls, to name a few. As a fe-male musician, I am really interested in this, because obviously throughout my career I’ve always experienced myself as periphery — in terms of finding myself as a female and being very determined and focused to make music no matter what. What was your decision to draw in all those other elements, was it to contextualise The Raincoats on a global stage?

Jenn Pelly: This stuff is my life. It is the world I choose to exist in most of the time; the constellation of feminist music and punk and art throughout history. So that’s where I’m coming from, and in the book I made intuitive connections to other works. As a shy outsider girl The Raincoats makes me feel like I’m not alone and I wanted to draw on other areas of culture that make me feel similarly. So I found ways to connect their music to the likes of Cindy Sherman and Pauline Oliveros and Agnes Varda and Virginia Woolf. I’m not sure exactly how many books about punk have been written from this perspective, but certainly there are more punk histories available from male perspectives.

What do you hope people get from reading the book?

I hope the book can help people understand the historical significance of The Raincoats. I’ve spoken to a lot of people who understand The Raincoats as a cool little-known band with a cult fanbase, which is true, but they have also helped to shape so many crucial areas of independent music — riot grrrl, indie pop, queercore, all of which pried open notions of punk and DIY to new ways of thinking about playing. I hope the story of The Raincoats would inspire someone to find their own voice.

When I was 14, growing up in Australia in the 90s, knowing of record labels such as Kill Rock Stars, Rough Trade, and through that The Raincoats, was the first time I had actively engaged in female-fronted music. I guess they did stretch to the far reaches of the world, and at the time were so necessary for people like me and other young, afraid, shy females to do things. They definitely did make a huge impact — because a lot of those people have grown up and gone on to have the confidence to make music and be creative, and I feel that they definitely played a very pivotal role in that, because they were all women.

This is why I wanted to write about the first Raincoats album. The Raincoats weren’t an all-female band for long. The debut album is actually the only one that has all women playing on it. Later they brought men into the fold.

How did the book formulate in your mind and how did the initial research process develop?

I first interviewed The Raincoats in 2011 when the band reissued their second album Odyshape. I remember coming out of that interview thinking, “I can’t believe there’s no book about this band.” I had the idea after that conversation, it seemed obvious to me. I’ve always felt viscerally connected to The Raincoats, like their music was an extension of myself, and I relate so much to that first record in particular. It has always felt like a reflection of who I am and how I see myself in the world. I’m a shy person and I spend a lot of time by myself. I’ve always identified strongly with the rhythms of living in the city, walking around alone with your thoughts, that sort of thing. Those are all big themes of my life. The idea of writing a book about The Raincoats for the 33 1/3 series appealed to me for a few reasons. The proposal process is outlined on their website so I knew how to pitch one. Also, a lot of 33 1/3 books focus on records that you’d assume are part of ‘the canon’ like Dylan, Bowie, Eno, etc. You might not expect a feminist DIY punk record to exist in that context, which I liked. I also liked the idea of keeping the book short; I’d hope that someone who is not already a converted Raincoats fan might be intrigued enough to read it. I chose the first Raincoats record because I’m interested in the genesis stories of bands. I’m inspired by the stories of how bands begin, and how people who didn’t previously play music find it within themselves to have the confidence to express themselves. It’s why a book like Our Band Could be Your Life was inspiring to me when I first read it — it was the story of the beginning of all these bands

There is something magical about a musician feeling their way through creating rather than knowing what to do. It’s a time that is rather hard to encapsulate. Do you feel that the beginning of that band was part of the appeal because they were so unique at that time and place?

I was interested in exploring how this record is the sound of four people working together and negotiating their differences. In a way, each of the four musicians are singing; they all have their own voice. The sound of the instruments is nonhierarchical. It was interesting for me to learn about Ana da Silva and Palmolive’s backgrounds growing up in Portugal and Spain. They were coming from these oppressive dictatorships, which made the freedom of London and punk even more appealing. Palmolive told me that democracy was “nonnegotiable” for her when she arrived in London and became involved with punk. Once I started learning about who these four women are as people, their backgrounds and experiences, I felt like I could hear four really strong personalities playing out on the record. They are all pushing the songs together and singing through their instruments. You can hear that they are working together and figuring it out together. And at best that’s what life is like: working with people and figuring out how to do things together.

You mention Chris Kraus in the introduction, who’s associated with the literary genre auto-fiction alongside Kathy Acker, Maggie Nelson and a few other writers. I’m interested in the concept of the ephemeral nature of The Raincoats playing, and the idea of them as collective authors of songs that were conceived as auto responses. What are your thoughts on this?

That’s cool to hear; I was reading books by Acker, Nelson, and Kraus while I was working on this. Actually, the wallpaper on my phone’s lock screen is a photo of Kathy Acker with The Spice Girls so I think about her all the time. Maybe it has something to do with how all of the music on The Raincoats was composed through improvisation and intuition. They were really listening to one another carefully and responding. Maybe it’s similar to automatic writing in that sense. I drew from I Love Dick in part because it captures this inspiring feeling of female interiority that I also hear on The Raincoats. I also think the Raincoats’ song ‘In Love’ presents obsession and infatuation in a similarly complex way. To paraphrase Kraus: it’s vulnerability as philosophy.

Chris Kraus uses elements of what could be conceived to be other people’s writing or voices, like conversations, emails and things like that, so it’s this pastiche of other voices that make up the final work. The Raincoats as producing the product that is a record, as a group, is very interesting because we don’t really think of musicians in that way. It is so magical what bands have, that they can write collectively — because in other mediums of creative art it’s perhaps more difficult…

To me the Raincoats album feels like a collage of sounds and emotions and poetry, springing from these four strong and distinct personalities. Ana is a visual artist, Gina is really into performance art and land art and conceptual art. Palmolive is really into poetry and the violinist Vicki brought a feminist vocabulary. So a book like I Love Dick — and the work of Kathy Acker and something like Maggie Nelson’s Bluets — it all feels collage-like to me, too. They are taking references to culture, literature, music, film and drawing these maps, presenting a way to be in the world. I wanted the Raincoats book to feel like a collage, too.

What is your favourite Raincoats song? You said earlier how that album connects with you as a person, its entrapped in your identity, is there any part of the record you could pinpoint as that defining moment?

There are so many different emotions on this album, so it’s hard to choose one song. But depending on my mood, ‘The Void’ or ‘In Love’ sound like the best songs I’ve ever heard in my life. Those songs capture essential truths about being alive. Some-times you’re low, sometimes you’re high. Sometimes you’re depressed, sometimes you’re floating. I really wonder if Chris Kraus has ever heard ‘In Love’ because I’ve never heard music that captures the feeling of infatuation better than ‘In Love’. It’s painful and beautiful and just a reflection of reality. Those two songs are pretty tied with ‘One More Hour’ by Sleater-Kinney as my favourite music in the world.

Words: Angie Garrick

Photography: Shirley O’Loughlin

Originally published in Oyster #113